THE VIETNAM WAR is a ten-episode, eighteen-hour documentary, running Sunday-Thursday on PBS for two weeks, beginning September 17. The project by filmmakers Ken Burns (THE CIVIL WAR, THE WEST, THE WAR, BASEBALL, etc.) and Lynn Novick has a scope that is at once historical and intimate, featuring interviews with war veterans, their families, politicians and experts on all sides: American, South Vietnamese and North Vietnamese.

In Part 1 of an exclusive phone interview, Burns discusses the making of THE VIETNAM WAR.

ASSIGNMENT X: How long were you and Lynn Novick working on this project?

KEN BURNS: About ten and a half years.

AX: Since the historical significance of the Vietnam War was evident while it was happening, even more so as soon as it concluded, why did you start working on this when you started, as opposed to sooner or later?

BURNS: I think as historians, or amateur historians, or whatever you want to call us, you always want to have twenty or thirty or forty years’ distance from a subject before you start making history about it. You just need that perspective and that much passage of time to be able to see things more clearly and enjoy whatever scholarship has focused on that period, and to be able to triangulate how to see it. We were finishing up a massive history on the Second World War, called THE WAR. It was scheduled to be broadcast in the fall of 2007, but at the very end, December of 2006, as we could see the light at the end of that tunnel, I just looked up and said, “We have to do Vietnam next.” And everything has sort of plowed towards that. Vietnam’s significance was, as you said, evident while it was happening, it was certainly evident in the failure of the U.S. objectives. And I think most people have tended to ignore it and bury their heads in the sand about it – understandably, forgivably, I suppose – or they’ve put themselves in hardened silos of certainty about a particular political point of view on it. And that’s unfortunate, and I think many of the seeds of division that we experience today were sown during the Vietnam War period, and perhaps it will be possible for us to kind of unpack what we think we know about Vietnam, and then repack it, benefitting from the new scholarship by the willingness of the veterans on all sides, and people involved, to speak about it, and access to Vietnam and its archives.

And so, if you think about it, if you did it ten years after the fall of Saigon, in 1985, America’s in a recession, Japan is ascendant, we’re talking about the Pacific Rim. Vietnam would be this ball on the chain that we would drag around for the rest of our history, this symbol of our inevitable decline. If we’d waited twenty years, until 1995, we were in the middle of the biggest peacetime economic expansion in U.S. history. We were the lone superpower, the Cold War was over. Vietnam would have importance, but it wouldn’t be this ball and chain, it wouldn’t be this symbol of our decline. In fact, we were “new vistas and new horizons.” If we’d waited thirty years, until 2005, we’d be engulfed in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the metaphors about Vietnam would be recurring. “We’re getting bogged down,” “It’s a quagmire,” “Isn’t this like Vietnam?” We were in a new anxious time, a new kind of not Cold War, but at least because of global terrorism and rogue states and rogue actors, we were feeling more vulnerable, and of course, it was just four years after 9/11.

So you begin to realize that the farther away you get from an event, the more you’re able to not just respond in the moment to what you think that event means, and you’re able to have a little bit more objectivity as you’re able to gather the facts. The last forty-two years, since the fall of Saigon, has seen enormous scholarship about every single aspect, whether it’s presidential administrations and their policy, the presidential tapes themselves, or their scholarship about Vietnam. Some of their archives have opened up that we’ve been able to take advantage of, and so we’re learning more about the dynamics in Hanoi and Saigon, as well as the dynamics in Washington. And all of this conspires to make it a better film.

outh Vietnamese troops fly over the Mekong Delta in 1963 from the Ken Burns documentary THE VIETNAM WAR |photo Courtesy of Rene Burri/Magnum Photos

AX: Many North Vietnamese people speak in the documentary. Was it difficult to find them, or are these people now well-known enough in Vietnam that, when you went there, the locals suggested, “Oh, talk to these people”?

BURNS: It’s sort of in between. This is what [Burns and Novick] do for a living: we track people down. It’s not easy, even on the American side, to find the right cast of characters to represent all the various experiences of the Vietnam War, whether it’s a Gold Star mother, or someone opposed to the war, or a journalist, or a policy wonk, or a helicopter pilot, or a Marine grunt, or an Army grunt, whatever it might be, and we’ve got them all in the film, representing their experiences. In Vietnam, we just had the difficulty of both culture and language, but we enjoyed rare access to the country, and we engaged the services of a wonderful Vietnamese producer, and they, like us, have veterans’ groups and reunions and things like that, so as our narrative was developing, we might say, “Can you find us somebody who was in the Battle of Binh Gia?” You might interview fifteen people before you find the person that you put on film to interview, or the five people that you put on film to use one of them to help us understand, in addition to the ARVN [Army of the Republic of Vietnam – South Vietnamese] soldier and his U.S. Marine advisor, and all of a sudden, the battle of Binh Gia comes alive, because you’ve got three different perspectives, happening at once in the moment. And that’s what you look for as a filmmaker, and that’s why this took ten years – to get the scholarship right, to find those archival images or the archival footage, to talk to and discover those people, and then you find a way to do simultaneous translation of the Q&A, they respond – we asked the same questions we asked our American counterparts. The experience of war is the experience of war, and once they can trust you, once they can see that you’re interested in a person dynamic, that we don’t have some political agenda, that we’re just interested in understanding what they felt and what they saw and what they did and who their parents were and who they loved and who they were worried about, then it becomes like any war story.

AX: You talk a lot with the Gold Star family of Denton Crocker, Jr. Is he well-known for something, or are they just the most articulate family you found?

BURNS: We did a lot of research. Sometimes Gold Star mothers and fathers and family members would write out little memoirs of what’s going on, to help with their own ongoing and continuous grief, and we had been aware of some things that Jean Murray Crocker had written, and we reached out to her as we did to other people. We did not know then how unbelievable she would be, and what a great gift it is. It’s not so much that it is some super story, it’s just the willingness of her to relive for us a date she does not have to relive for us, because it’s so painful, to make come alive a young man, and you can see that pain etched over her face in every single moment of every single time she’s on camera. And it’s heartbreaking. And yet, by doing it, she gives us – the filmmakers first – an extraordinary gift, which we felt honor-bound to carry like a delicate vase through the process of making this film, and I think by extension she gives an amazing grief as a gift to everyone, not only to those families that have suffered losses themselves in war, particularly in Vietnam, but to the rest of us, to understand the contours and immensity of grief.

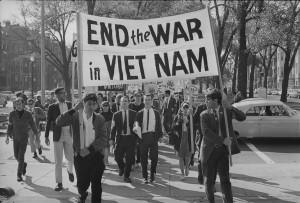

College students march against the war in Boston. October 16, 1965 from the Ken Burns documentary THE VIETNAM WAR | photo Courtesy of AP/Frank C. Curtin

AX: Is there an element of in sharing her story of letting Denton Crocker’s memory live on?

BURNS: I suppose so. For us as storytellers, what we try to do is free ourselves from whatever baggage we have going into it, to shed the conventional wisdom that will get in the way of us telling a clean story and a story that’s more accurate, and then to try not to put the arrows of meaning towards them. There’s a moment in her first on-camera bite at the beginning of Episode Three, in which she’s reading to her son from the St. Crispin’s Day speech in HENRY V by Shakespeare. And all of a sudden, you see this flicker pass across her face. That’s of course the famous speech where, “Those of you who aren’t here won’t feel as manly as those of us who are here.” You just kind of see again, “Oh, God, what did I contribute to him wanting to go over there?” And it’s a purely intimate moment. We don’t in any way, as I say, point arrows at it. But to me, it’s so, so powerful, and that’s what you want to get at.

When you doing stories about war, people tend to focus on the obvious conflicts. It is essentially about conflicts between tribes, between countries, between armies. And yet what’s most interesting is the psychological conflict that goes on within Denton Crocker Jr., that goes on within families, and within our Marine, John Musgrave, and within Jack Todd from Nebraska. All of these things happening within a person, their individual wars they’re trying to negotiate, and collectively, they can help us understand the larger wars, the movement of troops, the policy decisions, the courageousness or the lack of courage on the part of people. That to me is the great gift of studying wars, the inner thing. And I think you’ll find that, if you look at it, the literature of war is, yes, about what happened, but it’s also about what happens inside a person, not just outside.

AX: Do you identify at all with Vietnam war combat journalist Joe Galloway in terms of your job, or do you think that his job as a journalist is an entirely different sort of job than yours?

BURNS: Look, I work really, really hard. These are really, really difficult things. But I didn’t do what Joe Galloway did. I didn’t, twice within a few weeks, hop on a helicopter, head in towards danger sitting on a crate of grenades, and then being handed, on the first helicopter trip, a machine gun and told how to use it and clean it by the commander there, who’s under assault. Joe Galloway is in a special class of his own. I know a hero when I see one.

AX: There are moments where you show reel to reel tape recorders. Is that just to indicate that we’re listening to an actual tape recording, or is that because you felt that an image would distract from what was being heard?

BURNS: Sometimes you hear the tapes over exteriors of the White House, or pictures of Johnson on the phone, or Johnson in the office, or Nixon. Sometimes you see the tape recorder. We felt there was a dynamic that happens. We researched what kind of tape recorders would have been used to play back these tapes, they’re of the period, and yet there’s an intimacy with all of that going on. And I think because these tapes were made in secret, so much so that both Johnson and Nixon forgot they were being made – they would of course be Nixon’s undoing, and in some ways, they also contributed to Johnson’s undoing historically, in retrospect, but he still remains an extraordinary president, in terms of the other accomplishments of the administration. But it’s whatever worked for us as filmmakers.

At some point, the intimacy, the close-up dissection, helps you hear what’s being said without distraction, but it also focuses on the intimacy of what’s being captured, and that’s important. Sometimes, we’ll just be looking at a color shot that we took of the exterior of the White House, or an archival shot of the White House at night, or whatever we thought would be appropriate to that particular moment. At the end of the day, that is what works to communicate the story in terms of accuracy and emotion and the larger ebb and flow of the narrative.

Related: THE VIETNAM WAR Exclusive Interview with filmmaker Ken Burns – Part 2

Follow us on Twitter at ASSIGNMENT X

Like us on Facebook at ASSIGNMENT X

Article Source: Assignment X

Article: THE VIETNAM WAR Exclusive Interview with filmmaker Ken Burns – Part 1

Related Posts: